An analysis of crash and injury data collected by the National Automotive Sampling System Crashworthiness Data System between 1998 and 2015 in the United States, conducted by the University of Virginia, revealed a disturbing disparity: belted women are 73% more likely to be seriously injured in frontal crashes than men.

The research team explains that traditionally, car design and safety testing regulations have focused on men without considering the differences in women’s anatomy. Unfortunately, there is still no standard or specification for a female crash test dummy, although progress has been made on a prototype developed as part of a European research project.

This news raised important questions among car manufacturers, consumers and quality institutions. Similar situations also started to be detected with other products, such as safety elements in construction and bulletproof vests, among many others. It invites us to think about how quality infrastructure (QI) services can positively impact reducing gender gaps and promoting a more equitable world.

Quality Infrastructure and the Gender Approach

UNIDO states, “Setting up a Quality Infrastructure System is one of the most positive and practical steps a developing nation can take on the path forward to developing a thriving economy as a basis for prosperity, health and well-being”. QI organisations play a catalytic role in improving the quality of products and services, ensuring that they are safe and effective for all people, regardless of gender differences.

However, “there still seems to be a widespread perception that development measures in the field of quality infrastructure are gender-neutral.” This is suggested by a recent guide commissioned by the German Metrology Institute (PTB) to understand better the potentials and challenges associated with implementing the Feminist Development Policy, adopted by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and to be implemented in the context of the international cooperation department, section 9.3 of PTB. At the beginning of 2023, in the context of the adoption of the strategy for Feminist Development Policy, the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) declared gender equality and dismantling discriminatory structures a key priority of German development cooperation.

What would a gender perspective for QI services imply?

It means considering, for example, physiological differences and practical gender needs during the product design, testing, and certification process. In the case of automobiles, this could mean crash tests using dummies that more accurately represent the physical and behavioural characteristics of people of different sexes, sizes, and ages, among other characteristics that represent the diversity of users of a product or service.

In addition, a gendered approach would help to identify and eliminate unintended biases in regulations and conformity assessment procedures, ensuring that all users benefit from the same levels of safety and performance. This is particularly relevant in health, safety, and technology sectors, where gender differences could significantly impact the effectiveness and safety of products and services.

Counteracting existing inequalities and positively contributing to gender equality not only contributes to achieving equality but can also lead to general innovations and improvements in the design and functionality of products, thus favouring the competitiveness of companies using these quality services.

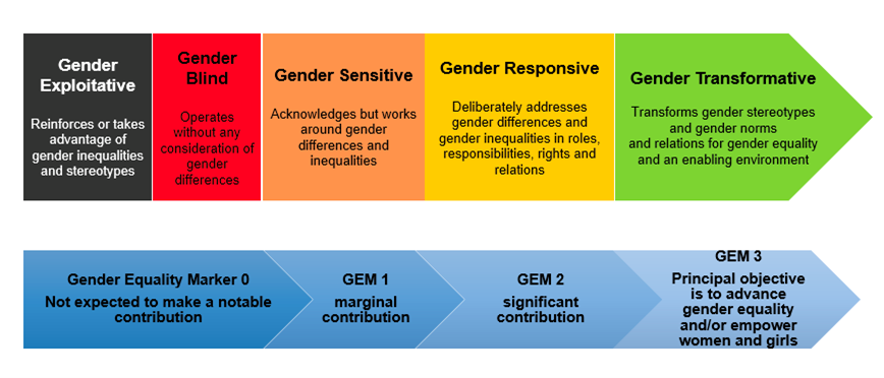

Mainstreaming a gender perspective is a transformative process that involves various aspects and contributions from organisations at different levels. QI services and actions could be analysed in terms of their degree of contribution to gender equality. A framework that conceptualises this practice is the “gender continuum” used by UNICEF to assess the contribution of its programs and projects to gender equality and the empowerment of girls and women.

Source: UNICEF Gender Equality Marker and Gender Tag Guidance Note (2022)

The ‘gender continuum’ model illustrates different approaches to addressing gender in programming and evaluation. It ranges from gender discriminatory to gender transformative:

Gender-discriminatory: This approach favours one gender over the other, thereby deepening gender inequalities. For example, focus groups exclude women on the assumption that only men can make decisions about households or communities.

Gender-blind: This approach ignores gender in programme design, perpetuating the status quo or potentially exacerbating inequalities. For example, conducting focus groups with all community members could put different groups at risk when discussing gender norms and roles.

Gender-sensitive: This approach recognises gender inequalities but does not address them in a robust way. An example would be conducting separate but identical focus groups for men and women, asking the same questions without exploring gendered experiences.

Gender-responsive: This approach identifies and addresses the different needs of girls, boys, women and men to promote equal outcomes. For example, it conducts separate focus groups at appropriate times for each group, tailors questions to bring out gender differences, and provides childcare and transportation.

Gender-transformative: This approach explicitly seeks to address gender inequalities, remove structural barriers and empower disadvantaged populations. It includes consultation with diverse stakeholders, consideration of intersectionality, participatory analysis and validation of findings to challenge discriminatory gender norms and power relations.

The continuum emphasises that international development projects should aim to be gender-responsive or transformative to promote gender equality across all sectors and evaluations effectively.

Alongside this tool are numerous entry points for gender main-streaming in QI, which we will discuss in another post.

Additional resources:

United Nations (2023), Unleashing the power of gender equality: Uplifting the voices of women and girls to unlock our world’s infinite possibilities

Reconsidering standards: female crash test dummies

ISO, Gender-sensitive standards: a guide for ISO and IEC technical committees

BMZ, Feminist Development Policy (BMZ)

Special thanks to Monica Muñoz for researching and co-writing this text.