Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) is a systematic approach to critically assessing the positive and negative impacts of proposed and existing regulations by systematically examining different policy options and alternatives. It is the only tool for Good Regulatory Practice (GRP) and an evidence-based approach to policymaking.

Quality Infrastructure (QI) includes standards, conformity assessment and metrology, and also technical regulations. QI functions aim to facilitate trade and have an international orientation by default.

The OECD recognises the relationship between GRP and standards in its typology of International Regulatory Cooperation (IRC):

Figure 1. OECD typology of IRC mechanisms.

Source: International Regulation Co-operation, OECD Policy Brief, OECD Regulatory Policy Division, 2018.

From a regulatory perspective, the QI elements of technical regulations, standards, conformity assessment and metrology provide non-tariff measures for the classification of NTMs in the UNCTAD Trade Analysis Information System (TRAINS)[1]. The UNIDO Technical Regulation Framework[2], the World Bank NTM Review Process[3], and the UNCTAD Toolkit for Assessing the Cost-Effectiveness of NTMs 4 are all based on and explicitly incorporate RIA.

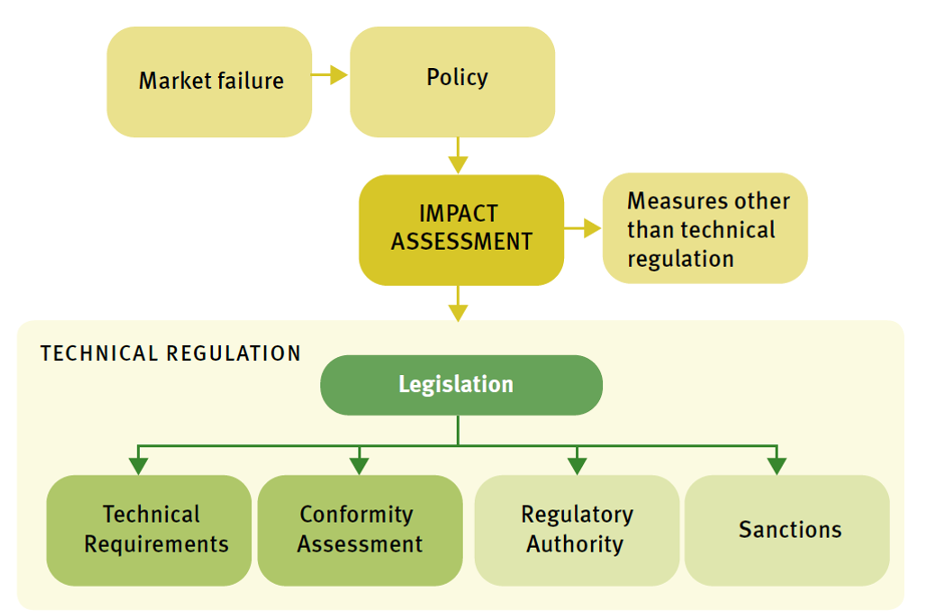

The UNIDO’s technical regulation framework states as one of the three building blocks that “RIA must determine whether the proposed technical regulation will adequately deal with the market failure, whether all of society will benefit if implemented, can the technical requirements be managed in the country and what the total costs and benefits will be. It should also consider the possibility of dealing with the market failure in ways other than using a technical regulation.”[4]

Technical regulations are also justified to protect rights, distribute benefits equitably, provide public goods, stimulate innovation and proactively shape new technologies and industries in line with societal priorities.

Figure 2. UNIDO’s Technical Regulation Framework.

Source: Quality Policy – Technical Guide, United Nation industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), 2018.

Divided into SPS & TBT measures, the WTO also encourages using RIA. For example, Article 2.2 of the WTO-TBT Agreement[5] stipulates the need of an assessment of available regulatory and non-regulatory alternatives to a proposed technical regulation that would meet the Party’s legitimate objectives and seeks to assess, inter alia, the impact of a proposed technical regulation through a regulatory impact assessment, as recommended by the Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade established under Article 13 of the WTO-TBT Agreement. The Guidelines on Conformity Assessment Procedures (G/TBT/54), recently adopted at the Committee’s meeting of 13-15 March 2024, states that a “risk assessment may include associated regulatory impact assessment (RIA) analysis, as part of good regulatory practice” (see footnote 2 of the Guidelines).

For example, in 2012, the Committee recommended mechanisms for assessing policy options, including the need for regulation (e.g. how to assess the impact of alternatives through an evidence-based process, including regulatory impact assessment (RIA) tools).[6] The WTO TBT Committee’s Life Cycle Approach to TRs also encourages using RIA.

SPS and TBT notifications should be submitted via the e-Ping platform. The notification requires, as one of three steps, an impact assessment to determine whether the measure may significantly affect trade and whether notification would be proportionate to the proposed TBT measure.

Figure 3. Notification procedure template of SPS and TBT measures on the e-Ping platform.

Source: WTO, Technical Cooperation Handbook on Notification Requirements, June 2022.

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), international agreements, and international organisations require RIAs, and a case in point is the EU-Vietnam FTA (EVFTA). Article 5.4.1 of the EVFTA adopts the provisions of the WTO-TBT Agreement, stating that each Party shall make best use of best regulatory practices and assess the impact of a proposed technical regulation through a regulatory impact assessment. Another example from a slightly different angle, is the country of Georgia, which in the context of the EU Association Agreement applied RIA to the EU Construction Product Regulations and associated relevant HS codes in sub-sectors of the construction industry to prioritise these, based on the impact of the application of HS codes.

Finally, international organisations such as the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) include the existence of an RIA practice in their ranking of countries; the ranking is important for the relevant institutions in a country (as noted in recent reports from Pakistan), for example, to attract foreign direct investment.

Examples of challenges in the QI domain RIA exposes

- Trade facilitation. RIA may expose and guard for non-tariff measures that are becoming (unnecessary) trade barriers.

- Identifying regulatory gaps. On paper, sufficient legislation is usually in place.

A recent study among SADC Member States shows that international standards are incorporated in technical regulations. However, secondary regulation may be lacking, hence the legislation’s implementation. RIA exposes these regulatory gaps, as well as it determines how the piece of regulation ‘sits’ within the broader regulatory framework, also potentially identifying gaps between laws and regulations.

In Cote d’Ivoire, overall, the legal and regulatory framework for the National Quality Infrastructure has reached a very elaborate and satisfactory level. However, secondary regulations, which should concretise these laws, are not in place yet.

Regulatory gaps contain, for example, designating the metrology institute(s) as well as accreditation and standardization organisations in legislation, providing financial autonomy to these organisations and re-define their roles such that they become financially self-sustainable, market surveillance improvement and coordination, and develop and strengthen conformity assessment bodies. - Concentrated QI service provision. In Saint Lucia, the functions of the Saint Lucia Bureau of Standards include ‘all’ QI elements: standards development, conformity assessment through verification and certification. This confuses conflicts of interest and legal liability. Legal ‘firewalls’ would be needed to separate the QI elements.

- Differentiated QI service provision. Zambia has a Standards Act (2017), a Compulsory Standards Act (2017), and a National Technical Regulation Act 2018. The Zambian Compulsory Standards Agency (ZCSA), residing under the Ministry of Commerce Trade & Industry (Industry), is responsible for administering the Compulsory Standards Act. ZCSA has taken over the ZABS Inspections Department. The Department of Technical Regulation in the Ministry of Commerce Trade & Industry (Trade) administers the National Technical Regulations Act. This situation may confuse conflicts of interest and regulatory and institutional overlap.

- Fragmentation of QI regulations. QI is usually regulated in a host of Acts concerning plant health, animal health, food safety, goods control, trade, etc. These involve many regulators, which results in many (compliance) obstacles. To tackle this issue, for example, in Uganda, the so-called Rationalisation Bill is currently in draft, considering eliminating (or merging) a considerable number of regulators (in particular, agencies, authorities, etc.)

- Challenges regulators face in the QI domain correspond ‘naturally’ with the steps of the RIA process, such as problem definition, the (justified) purpose of the regulation, consultation, and implementation.

Examples of Implementation issues in the QI domain RIA exposes

Internationally:

- Trade facilitation measures would include, for example, pre-arrival and pre-departure declarations, effective sampling, risk management and document-based controls. Data management is critical to these measures, with three main elements: identifying risk indicators, sharing and using data to better manage risk, and outcome-based rather than process-based regulation.

- Pre-shipment inspections. The WTO Bali Trade Facilitation Agreement of December 2013 discourages pre-shipment inspections. The agreement prohibits pre-shipment inspections where the procedure is used to determine tariff classification and customs valuation. However, other types of pre-shipment inspection are still allowed, although Member States are encouraged not to expand the practice (Article 10.5). However, in Egypt, for example, Decrees 991/2015 and 43/2016 have extended the practice of pre-shipment inspections due to the extension of the list of regulated products.

- Exports. QI regulations do not only apply to imports. For example, the Tanzania Revenue Authority (TRA) regulates agricultural products for export. The process involves monitoring the raw material, the production process, and loading, and when all the documentation is in place, the TRA issues a Customs Release Order. This is done in coordination with the Tanzania Ports Authority (TPA), clearing agents and shipping lines. The TPA issues a permit for the goods to be allowed on the port premises. The Tanzania Atomic Energy Commission (TAEC) provides an atomic radiation certificate (issued per consignment of goods); this is presented as an international requirement, mainly for “in-country security purposes” (although many destination countries do not have such a requirement). Overall, the control function for agricultural exports focuses on ensuring that agricultural goods destined for export (often at favourable tariffs) do not return to the local Tanzanian market.

Domestically:

- Technical regulations are developed for the same product by different regulators. For example, in Vietnam, there are 12 lists of regulated goods from line ministries involved in developing technical regulations. These lists sometimes include the same products, e.g. milk additives are regulated by the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the Ministry of Health, paints are regulated by the Ministry of Industry and Trade (mainly on chemical composition) and the Ministry of Construction and Public Works, and some agricultural machinery is managed by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Transport. As a result, different technical regulations apply to these products. This leads to overlap in testing, problems with duplication of laboratory testing, recognition of test results, and designated laboratories.

- There is a need to harmonise terms (between regulations) and correct classification of goods. Confusion arises, for example, when chemicals are not correctly registered (regarding the CAS code) and may even have different names.

- Inspection regime and capacity. In the Solomon Islands, for example, there are diffuse mandates for the inspection of standard products: the Consumer Affairs & Price Control Division of the Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Labour and Immigration (MCILI) can inspect but not confiscate. Confiscation is the responsibility of the Ministry of Health & Medical Services.

- Effective implementation of QI measures. For example, the Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS) is known for delays in issuing quality marks to (domestic) private sector producers, which affects market access. One juice manufacturer reported waiting more than two years for a Q-mark to be issued, diluting its investment.

Conclusion

Given the wide range of international institutions, organisations and agreements that either require or encourage RIA, RIA cannot be an all-encompassing solution to all QI-related regulatory issues. After all, RIA comes into play when there is regulatory intent, with a piece of regulation as the subject (“we regulate, unless”).

However, QI can benefit from RIA because the application of RIA leads to greater transparency about the (predicted) impact of regulations, which allows for better regulations and leads to better QI systems, which improves the impact of QI itself.

RIA helps to move from command-and-control regulation to market-oriented regulation by focusing on the impact of regulation on the target group of the regulation; it helps to identify distributional aspects, address unintended consequences, identify barriers to trade, etc.

National standard-setting bodies can explicitly encourage using RIA, as recently done in Vietnam’s new NQP. Regulators, such as ministries, should apply RIAs to their technical regulations.

[1] UNCTAD. Trade Analysis Information System (TRAINS) database. Available at https://trains.unctad.org/.

[2] UNIDO, Quality Policy – Technical Guide, United Nations Industrial Development Organization, 2018.

[3] The World Bank, Streamlining Non-Tariff Measures a Toolkit for Policy Makers, 2012.

[4] UNIDO, Quality Policy – Technical Guide, United Nations Industrial Development Organization, 2018.

[5] WTO-TBT Article 2.2: “Members shall ensure that technical regulations are not prepared, adopted or applied with a view to or with the effect of creating unnecessary obstacles to international trade. For this purpose, technical regulations shall not be more trade-restrictive than necessary to fulfil a legitimate objective, taking account of the risks non-fulfilment would create. Such legitimate objectives are, inter alia: national security requirements; the prevention of deceptive practices; protection of human health or safety, animal or plant life or health, or the environment. In assessing such risks, relevant elements of consideration are, inter alia: available scientific and technical information, related processing technology or intended end-uses of products.”

[6] G/TBT/32, 29 November 2012, para. 4.

The QI4D hosts regularly invite experts from neighbouring areas of quality infrastructure to share their knowledge on our blog QI4D.

Our guest author is Dr Kees Roeland Jonkheer, an international expert on regulatory impact assessment, regulatory reform and private sector development. He considers himself a “regulatory geographer” with an MSc in Economic Geography and two additional certificates in European Trade Law and a certificate in Regulatory Impact Assessment.

Dear Sir Thanks a lot for your mail and for sharing too.Will peruse and revert back. Regards Sammy Milgo

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike